Abacus, usually a square uppermost part of a capital..

Abbey, a church or chapel of a monastery.

Aisle, the side of a nave (q.v.) separated from the nave proper by a colonnade.

Ambulatory, passageway around the choir, often a continuation of the side aisles of the nave.

Apse, a semi-circular or polygonal vaulted space behind the altar.

Apsidiole, small apse-like chapel.

Arcade, a series of arches carried on piers or columns.

Barrel vault, semi-cylindrical vault with parallel abutments and of constant cross sections.

Basilica (1), a rectangular building with a central nave, side aisles separated by colonnades, with or without a transept, (2) Roman Catholic Church that has been accorded certain privileges by the pope.

Bay, a vaulted division of a nave, aisle, choir or transept along its longitudinal axis.

Blind (arch, arcade), an arch or arcade with no openings, usually as decoration on a wall.

Boss, a projecting stone at the intersection of ribs, frequently elaborately carved. Its function is to provide a net intersection of the ribs and tie them into one unit.

Buttress, a masonry member projecting from a wall, rising from the ground, and counteracting the outward thrust of the roof or vaulting. In Gothic architecture, a flying buttress is a freestanding element connected by an arch to the outer wall.

Canopy, a protective roof above statues

Campanile, term only applied to a bell tower which is detached from a church..

Capital, the head of a column.

Cathedral, the chief church of a Diocese (Roman Catholic or Episcopal) which contains the Cathedra, the seat of the Bishop.

Chancel, interchangeable with choir (q.v.), sometimes the area in front the altar.

Chevet, an apse (q.v.), typically the ambulatory (q.v.) and radiating chapels (q.v.).

Choir, area at the end of the nave which is reserved for clergy or monks (modern - singers), and which contains the altar and choir stalls.

Choir stalls, the row of stepped seats on either side of the choir, facing inwards.

Cinquefoil, a figure of five equal segments.

Clerestory, the exterior wall of a nave above the level of the aisles with windows.

Cloister, quadrilateral enclosure surrounded by covered walkways, the center of activity for the inhabitants of a monastery.

Close, the area on which the cathedral and subordinate building stand.

Columbarium, a structure of vaults lined with recesses for urns.

Concha, semi-circular niche with a semi-dome.

Corbel or Console, ornamental bracket that projects from the wall.

Crocket, an ornament consisting of a projecting piece of sculptured stone or wood. Used to decorate the sloping ridges of gablets, spires, and pinnacles. Usually carved as foliage.

Crossing, the area of a church where the nave is intersected by the transept.

Crypt, underground chamber beneath the altar in a church, usually containing a saint’s relics. It sometimes extends as far as the crossing, so that the choir and altar are sometimes considerably higher than the nave and aisle.

Engaged column, a column embedded in a wall, not free standing.

Finial, the topmost portion of a pinnacle, usually sculptured as an elaborate ornament with upright stem and cluster of crockets; seen at a distance, it resembles a cross from any angle of vision.

Galilee, a chapel or porch at the entrance to a church

Gargoyle, a pierced or tunneled stone projecting from a gutter and intended to carry rain away from wall and foundations. It is usually carved into the image of a beast or ugly creature.

Gallery, an upper story, running along the side of a church, open on one side to the interior.

Groin vault, type of vaulting caused by two equally large barrel vaults (q.v.) crossing at right angles; the angle formed by the intersecting vaults is the groin.

Intrados, the inner face of an arch or vault.

Lady chapel, a chapel dedicated to the Virgin Mary.

Lancet, a pointed arched window of one opening frequently arranged in groups of two to five.

Lantern tower, a tower with windows shedding light into the crossing (q.v.).

Lunette, a semi-circular space above doors and windows, sometimes framed and decorated.

Misericord, In the choir stalls of medieval church, a bracket (often grotesquely or humorously carved) beneath a hinged seat which, when the seat was tipped up, gave some support to a person standing during a lengthy service.

Narthex, the single-story porch of a church

Nave, the area of a church between the façade and crossing or choir, specifically, the central area between the aisles.

Niche, a recess in the face of a wall or pier, prepared to receive a statue.

Oculus, a small circular opening admitting light at the top of a dome.

Pier, a mass of masonry supporting an arch or vault and distinct from a column, A clustered pier is composed of a number of small columns.

Pinnacle, a turrent tapering upward to the top, its gracefulness enhanced by crockets (q.v.),and top stone called a finial (q.v.).

Pulpitum, a screen dividing the choir from the nave. Often called Rood Screen.

Predella, the step or platform on which an altar is placed.

Portal, a major entrance to church, emphasized by sculpture and decoration.

Quatrefoil, a figure used in window tracery, shaped to form a cross or four equal segments of a circle.

Radiating chapels, chapels leading off from the ambulatory, and arranged in a semi-circular fashion.

Reredos, the wall or screen at the back of an altar, either in carved stone, wood or metal.

Retrochoir, in some cathedrals, the portion of the chancel (q.v.) behind the high altar at the extreme east end.

Respond, long narrow column or engaged column, mainly in Gothic architecture, which supports the arches and ribs of groan vaults or the profiles of arcade arches.

Reliquary, a casket containing one or more relics.

Rib, a structural molding of a vault.

Rood Beam, a large beam set transversely across a church from north to south on which stands a crucifix.

Rood screen, the screen dividing the choir from the nave.

Rose Window, a round window, with tracery (q.v.) dividing it into sections, called petals.

Sanctuary, the part of the church which contains the high altar.

Sedilla, seats in the sanctuary (q.v.) near the altar, usually three in number for clergy.

Shaft, the main part of a column, from its base to its capital.

Spandrel, the triangular space between the outer curve of an arch and an enclosing frame of mouldings, often richly carved with foliage.

Tracery, a term for the variations of mullions in Gothic windows and for geometric systems on wall panels and doors.

Transept, section of a church a right angles to the nave and in front of the choir.

Trefoil, either a carved three-leaved ornament, or a three lobed opening in tracery (q.v.).

Triforium, space below the clerestory (q.v.).

Triptych, a picture, design or carving on three panels, often an altar piece.

Tympanum, the area above a portal (door) enclosed by an arch, and the most important site for sculpture on the exterior of the church.

Vault, the ceiling of a church formed of concrete, stone in mortar or brick in mortar forming a continuous semicircular or pointed arch.

Vesica, an aureole or pointed oval shape, surrounding a sacred image.

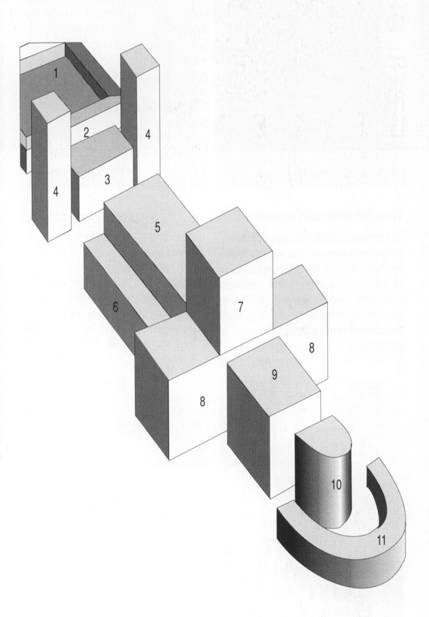

1. 1. Narthex or atrium

2. 2. Interior western section of forecourt has often been developed as the “Galilee”

3. 3. Narthex together with the

4. 4. West towers forms a twin-towered façade

5. 5. The central nave of the basilica is flaked by

6. 6. The two side aisles.

7. 7. The crossing is surmounted by a central tower.

8. This is also the point from which the arms of the transept start.

9. Continuing from the central nave, the choir extends eastward.

10. To this is connected the apsidal-ended sanctuary (apse) and in some cases also an

11. Ambulatory, often incorporating chapels.

Source link here.