Translate

Sunday, February 27, 2011

Thursday, February 24, 2011

Silk, Background and Production

"Silk has set the standard in luxury fabrics for several millennia. The origins of silk date back to Ancient China. Legend has it that a Chinese princess was sipping tea in her garden when a cocoon fell into her cup, and the hot tea loosened the long strand of silk. Ancient literature, however, attributes the popularization of silk to the Chinese Empress Si-Ling, to around 2600 B.C. Called the Goddess of the Silkworm, Si-Ling apparently raised silkworms and designed a loom for making silk fabrics.

The Chinese used silk fabrics for arts and decorations as well as for clothing. Silk became an integral part of the Chinese economy and an important means of exchange for trading with neighboring countries. Caravans traded the prized silk fabrics along the famed Silk Road into the Near East. By the fourth century B.C. , Alexander the Great is said to have introduced silk to Europe. The popularity of silk was influenced by Christian prelates who donned the rich fabrics and adorned their altars with them. Gradually the nobility began to have their own clothing fashioned from silk fabrics as well.

Initially, the Chinese were highly protective of their secret to making silk. Indeed, the reigning powers decreed death by torture to anyone who divulged the secret of the silk-worm. Eventually, the mystery of the silk-making process was smuggled into neighboring regions, reaching Japan about A.D. 300 and India around A.D. 400. By the eighth century, Spain began producing silk, and 400 years later Italy became quite successful at making silk, with several towns giving their names to particular types of silk."

The Silk Road: Linking Europe and Asia Through Trade

"Originally, the Chinese trade silk internally, within the empire. Caravans from the empire's interior would carry silk to the western edges of the region. Often small Central Asian tribes would attack these caravans hoping to capture the traders' valuable commodities. As a result, the Han Dynasty extended its military defenses further into Central Asia from 135 to 90 BC in order to protect these caravans.

Chan Ch'ien, the first known Chinese traveler to make contact with the Central Asian tribes, later came up with the idea to expand the silk trade to include these lesser tribes and therefore forge alliances with these Central Asian nomads. Because of this idea, the Silk Road was born.

The route grew with the rise of the Roman Empire because the Chinese initially gave silk to the Roman-Asian governments as gifts."

Silk Road, NY Times Article

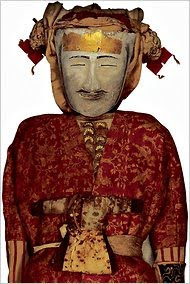

"This is the crux of the matter, for most bodies found in this region have what are called Caucasoid features. And though many objects here are clearly associated with later Chinese traditions — like the delicate figurines of women making pottery (from the seventh to ninth centuries) — others come from cultural worlds that can still not be clearly identified."

Monday, February 14, 2011

Sunday, February 13, 2011

Memorial to Washington, American Folk Art Museum

Click on above title to see image.

Artist unidentified

Eastern United States

Early 19th century

Ink, mica flakes, and mezzotint engravings on paper with applied gold paper, mounted on wood form

4 3/4 x 1 3/4 x 1 3/4 in.

American Folk Art Museum, gift of Nancy Green Karlins and Mark Thoman in honor of Robert Evans Green, 2001.15.1

George Washington’s death in 1799 was the first cataclysmic emotional loss suffered by the new American nation. Citizens mourned him at public memorial services or by fashioning commemorative objects to place in their homes. In time an industry rose up to meet the collective appetite for material imprinted with the images of departed public figures. Ironically, much of the production of ceramics, textiles, and objects lamenting the loss of America’s early heroes originated in England and was later copied by professional and amateur artists in America. This small handmade memorial to Washington is in the form of an urn with finial placed on a plinth, a neoclassical motif widely disseminated in the decorative arts by Josiah Wedgwood, Robert and James Adam, and others.

The urn became one of the basic building blocks of mourning iconography. Its symbolic association with the spirit of the deceased dates back to its origin as the vessel for the ashes and vital organs of the departed. This piece is a wooden form that is covered with paper. It is embellished with mica flakes, ball-embossed gold paper strips, designs in sepia ink, and portrait engravings, though only the engravings of Washington and Thomas Jefferson remain; the other two sides may have held portraits of John Adams and James Madison.

The portrait engraving of Washington is prominently placed on the front of the plinth and surrounded by a series of circles containing symbolic pictorial elements. Homages to Washington were still being created by schoolgirls as late as the 1820s, when Harriet Lenfestey stitched the following verse into her 1823 sampler: “Columbia lamenting the loss of her Son / who redeemed her from Slavery and liberty won / while fame is directed by Justice to Spread / The Sad tidings afar that washingtons dead.”

Artist unidentified

Eastern United States

Early 19th century

Ink, mica flakes, and mezzotint engravings on paper with applied gold paper, mounted on wood form

4 3/4 x 1 3/4 x 1 3/4 in.

American Folk Art Museum, gift of Nancy Green Karlins and Mark Thoman in honor of Robert Evans Green, 2001.15.1

George Washington’s death in 1799 was the first cataclysmic emotional loss suffered by the new American nation. Citizens mourned him at public memorial services or by fashioning commemorative objects to place in their homes. In time an industry rose up to meet the collective appetite for material imprinted with the images of departed public figures. Ironically, much of the production of ceramics, textiles, and objects lamenting the loss of America’s early heroes originated in England and was later copied by professional and amateur artists in America. This small handmade memorial to Washington is in the form of an urn with finial placed on a plinth, a neoclassical motif widely disseminated in the decorative arts by Josiah Wedgwood, Robert and James Adam, and others.

The urn became one of the basic building blocks of mourning iconography. Its symbolic association with the spirit of the deceased dates back to its origin as the vessel for the ashes and vital organs of the departed. This piece is a wooden form that is covered with paper. It is embellished with mica flakes, ball-embossed gold paper strips, designs in sepia ink, and portrait engravings, though only the engravings of Washington and Thomas Jefferson remain; the other two sides may have held portraits of John Adams and James Madison.

The portrait engraving of Washington is prominently placed on the front of the plinth and surrounded by a series of circles containing symbolic pictorial elements. Homages to Washington were still being created by schoolgirls as late as the 1820s, when Harriet Lenfestey stitched the following verse into her 1823 sampler: “Columbia lamenting the loss of her Son / who redeemed her from Slavery and liberty won / while fame is directed by Justice to Spread / The Sad tidings afar that washingtons dead.”

Asa Ames, American Folk Art Museum

Filling in the Contours of a Surprising Golden Age

Published: April 25, 2008

Collection of John T. Ames

A daguerreotype, the only known photograph of Ames, is full of references to his work and leisure.More Photos »

Enterprising self-taught painters of the period like Ammi Philips and Erastus Salisbury Field, who traveled around New England painting portraits for a living, have long been known in the folk-art world and beyond. Similarly determined sculptors are much rarer. Ames is an exception, though much about his life remains a mystery. He was born in 1823 in Evans, N.Y., a small town 20 miles south of Buffalo. His date of birth and death both come from his gravestone. And an 1850 federal census tantalizingly lists his occupation as “sculpturing.” He might have spent time at sea and been apprenticed to a carver of ships’ figureheads or trade figures. Until 25 years ago, Ames’s work, when noticed at all, was probably lumped together with such carvings. But in 1981 the American Folk Art Museum received an anonymous piece as a gift: a wood bust of a young girl whose head has a phrenology chart painted on it. Ms. Hollander ultimately attributed it to Ames. In 1982 Jack T. Ericson, an antiques dealer, culminated 12 years of research on Ames with an article in Antiques magazine. It reproduced the works that could be traced or attributed to him, including the folk art museum’s piece, which is thought to have been made at the end of Ames’s life, when he was ill and living with a doctor who practiced alternative medicine.

One of the show’s standouts was discovered only in 2003, in the basement of the Boulder History Museum in Colorado. Made in December 1849, it is a full-length portrait of Susan Ames, the daughter of his brother Henry G. Ames. Wearing a violet dress, Susan stands staunch and solemn, showing that posing was not much fun. Her eyes are intent but unfocused; she is holding still as best she can by thinking about other things. She has a small Bible or hymnal in her right hand; her left is raised.

The violet of Susan’s dress is boldly accented with a red collar, waist and hem; its gathers are round and regular, almost like the flutes on a Classical column. Her pantaloons are edged in eyelet lace whose holes have been carefully carved, as has the red upholstered footstool she stands on, right down to its brass-colored tacks. The colors and details imbue the entire sculpture with the intensity of Susan’s expression.

Ames’s artistry has a distinct personality. His work is full of signature tics, like his careful carvings of his subjects’ hair or ears. There is also a familial resemblance among the sculptures, and between them and Ames, as shown by the only known photograph of him.

Two of the best pieces in the show are sculptures of robust young men who might be Ames’s brothers or Ames himself. “Head of a Boy” is luxuriant with youth, from its thick, carefully combed hair (back from the brow, but forward on the sides) and flushed cheeks to its fine-looking jacket, tie and shirt. His dark, focused eyes and slightly pursed lips brim with ambition and hope; he seems to be practicing to look like a judge or senator. The slightly fairer subject of “Bust of a Young Man” is even more lifelike; here the pursed lips seem about to speak. He brings to mind the figures of the self-taught sculptor and photographer Morton Bartlett and Charles Ray’s mannequin sculptures.

Ames’s inspirations clearly included the portraits that itinerant painters were making during this period, but translating these wonderfully stiff, often emotionally fraught images into three dimensions gives them an added sense of life. The best of them have the artifice and complexity of 19th-century photographs, with which Ames had at least one close encounter.

The strange, beautiful and overpopulated daguerreotype that this encounter produced testifies to Ames’s ambition. He is in his Sunday best, working intently with a mallet and chisel on a bust of a man. (Its profile, near his knee, suggests a self-portrait.) Three sculptures look on from the upper right: a pudgy baby with a drape of fabric around its middle (it is in the exhibition, without the drape) and the busts of two other children, both in carved, off-the-shoulder togas in keeping with the neo-Classical style of the day.

The busts teeter on a textile-covered stand beneath which, peeking upward, is a young man, who might almost be another sculpture. The carving of a hand (also in the show) and real-looking bass viol visible behind this party of five increase the sense of elaborate stage-managing. Ames was probably ill when this photograph was made, and perhaps he knew that obscurity threatened. Packed with details about his leisure interests as well as his “sculpturing,” with his works doubling as an imagined audience, this carefully constructed image has the same intensity as Ames’s portraits. It is a detailed message in a bottle that he sent into the future, which is now.

“Asa Ames: Occupation Sculpturing” continues through Sept. 14 at the American Folk Art Museum, 45 West 53rd Street, Manhattan; (212) 265-1040, folkartmuseum.org.

Article from New York Times.

Friday, February 4, 2011

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)